“What I recall is a kind of longing – I felt everything I wished to say, even if I didn’t exactly know it. There was so much I did not understand and what I did understand I could never say with all the layers and color that would truly convey that understanding to my reader,” —Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Message, p. 129.

Hey there readers, thanks following and/or subscribing to The Nano, a publication about embodiment and writing for the sake of our collective liberation. If you’ve been here for a while, you know my public posts may be sporadically published, with a complex and wide range of subjects. Yet truly, at the root of all my writing work, is my love of words and composition. As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote in his newest book, The Message, “a love of language, of course, is the root of self,” (p. 4).

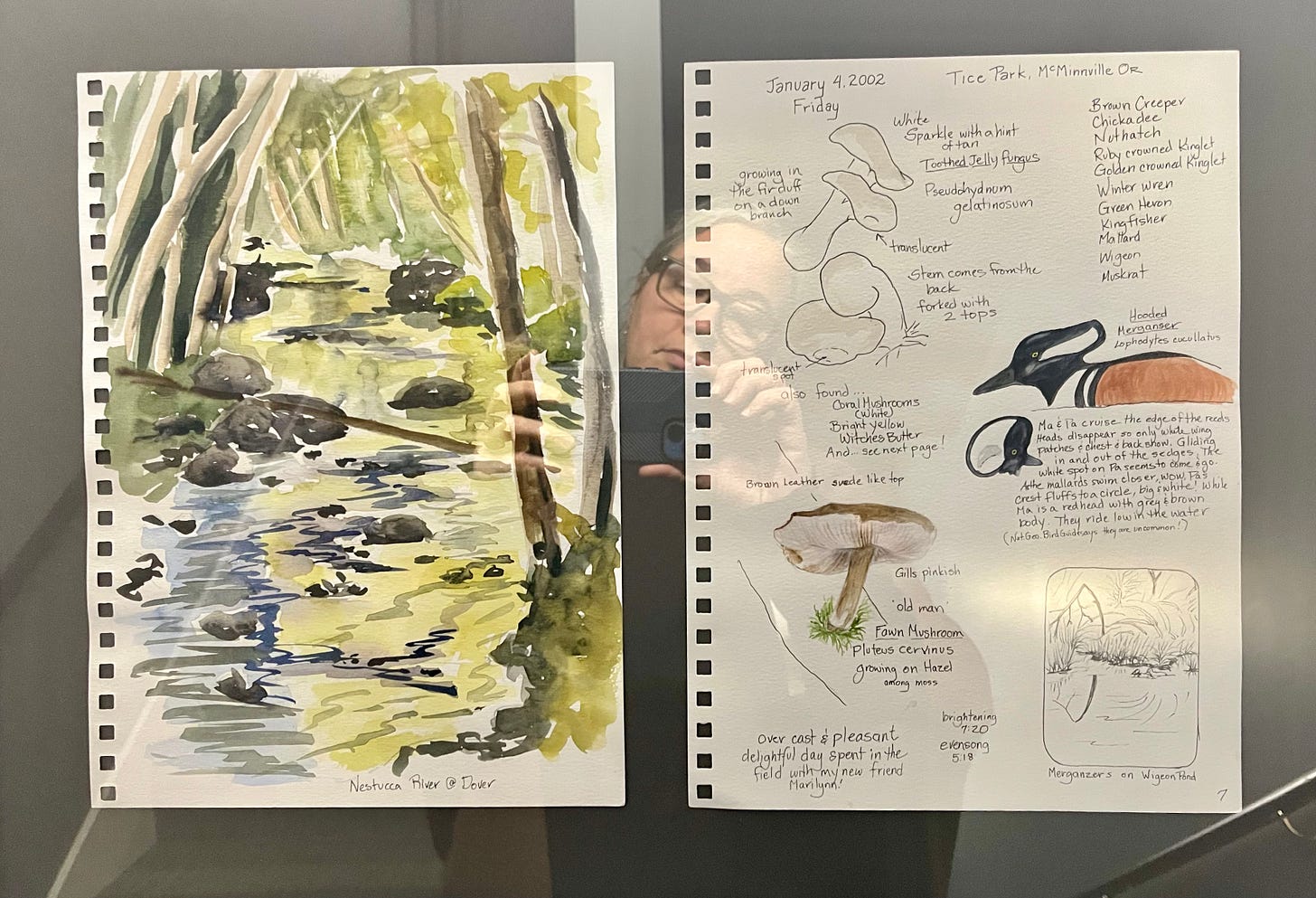

I’m reentering public life after two blessed weeks of private writing and headspace time through a new Artist-in-Residency program at the Atticus Hotel, a partnership with Linfield University in McMinnville, Oregon (thanks, Joe Wilkins). In all my years as a writer, I’ve never applied to a residency, and now I understand the value, as did Virginia Woolf: a room of one’s own is no joke.

Leaving my family during the first month of our government being torn apart gave me a lot of feelings. Arranging wonderful helpers, both volunteers and paid, to care for my mom (my spouse provides some, but also did/does a great deal of care for his mom living with dementia), was its own feat of carework. In my private room, I cried a ton because: grief.

I grieved how many friends, neighbors, and beloved strangers are being affected immediately and swiftly after the inauguration in a bombardment of exclusion, termination, deportation, defunding, attack, misinformation, and chaos; all intentional and planned and what America voted for. I grieved for the deaths and declines of my personal loved ones; my father-in-law, lost friends, and the anticipatory loss of my mom, dad, and mother-in-law. I grieved my own stuff, too, letting go, as we say in recovery, “of old beliefs, and the result is nil until we let go absolutely.” Reader, I absolutely let go of a lot.

Grieving and letting go, which is to say feeling, is critical work in these times, especially by those of us with full awareness of how our bodies are several degrees removed from all of the destruction happening at the moment and a clear recognition we will not remain removed for very long. I was both quite aware how I had the privilege to feel my feelings while also having all my basic needs met, i.e., rest and shelter, health and food, love and friends, and how this U.S. take down will expedite the collapse that was perhaps inevitable anyways because empires never last and climate feedback loops are real. Still, plenty of people haven’t had their basic needs and human rights met for eons.

Coates says, “Literature is anguish,” (p. 94), and that’s no joke either. Besides the intentional time to grieve, my goal for my residency time was to, in an adaptation of Cheryl Strayed famous words, “write like a fatherfucker.” (I’ve decided mothers have been fucked enough, sorry Mom and Cheryl.) I achieved Diana Keaton (in Something’s Gotta Give) levels of feeling and writing and putting stories together like a complex puzzle that I’ve been wanting to put together (longing, the longing) for years, decades even. I really am so grateful for my time.

Literature, at its basis, means stories. People’s stories, true or fictionalized in whatever form (poetry, essays, novels, maybe even newsletters), often come from a place of heartbreak and grief, where our longing to tell the story is an unmet but real need to be seen and heard. In the telling and writing down of the story, the pain and longing can transform into joy and connection and, if we’re lucky (and a tiny bit skilled), art. The transformation into art softens our bodies into the embrace of the human, creative life-force rather than the violence of the isolating, destructive death-wish. Staying in the life-force is an act of revolution, as is staying in our feelings. As Coates says, “the threat of the storyteller who came through words erodes the claims of the powerful,” p. 141. What more do we need right now than to erode the misleading, harmful, and straight up cruel claims of those in power?

In another adaptation of a famous phrase—”faith without works is dead”—I tend to believe art without action is in danger, as my mom says, of becoming “hotel art.” We do not need more hotel art, i.e., the art produced for product rather than for soul. The blues and jazz music that most moves us is because the lived experienced of the musicians, telling their stories, comes through the words and the song. (Shout out to the Atticus Hotel, by the way, for supporting that kind of soulful art, visible in many spaces of their facility.)

My many advantages and all my years with my basic needs and human rights met has allowed me to have capacity to jump into action, to show up with those most impacted by authoritarian leadership, and to put my body on the line.

I’m not only talking about going to a protest or two, although please do. I’m talking about the daily rigor of organizing with communities who need all of us to look around, see what is needed (rest, shelter, health, food, love, friends, etc.), be clear about what we can and cannot do, and then show up to do it. We need everyone doing the carework: making sandwiches at the shelter, facilitating meetings that include all kinds of opinions, making Know Your Rights posters, taking care of elders and children, putting a little free public library box up in your neighborhood, supporting your actual public library, and donating your time, talent, and treasure at as high a level as you can without burning yourself out or harming others in the process.

Coates says, “Politics is the art of the possible, but art creates the possible of politics. A policy of welfare reform exists downstream from the myth of the welfare queen. Novels, memoirs, paintings, sculptures, statues, monuments, films, miniseries, advertisements, and journalism all order our reality. Jim Crow segregation—with its signage and cap-doffing rituals—was both policy and a kind of public theater. The arts tell us what is possible and what is not, because, among other things, they tell us who is human and who is not,” p. 106.

I loved that paragraph because I’m an old radical feminist who still believes the personal is the political, so turning our stories into art is a political act of imagining. Plus Coates’s line reminded me of something Rebecca Solnit said after the first Trump administration, which was “political change often follows culture, as what was long tolerated is seen to be intolerable, or what was overlooked becomes obvious.”

I am responsible first for changing the culture of my body and by doing that, I can be a part of whatever cone of influence I have within a wider culture. By changing my actions; showing up where I have been absent, being a part of community when I feel isolated and alone, and speaking up where I have been silent, I am changed. The culture that created a country for and led by white, straight, able-bodied, educated, wealthy, U.S.-born, and propertied biological males is right now doubling-down on those identities as the sole recipients of this country’s benefits. In the process (since by 2040 the majority of people in America will not match those named identities), the current leaders are mistakenly not preserving a way of life I have and many others have tolerated, they are uncovering our mass intolerance to such narrow thinking.

We must make our intolerance known and loud, by telling our real stories, and by being in action with those whose intersections have the least crossover with and have been most pushed to the margins by, the dominant but dying culture. I want to be part of building and being a part of the culture of the life-force, the creative community, the place where love and care abounds.

How are you turning your story into art? How does community action inform your art and daily practices? I look forward to hearing your stories.

What a powerful essay, Nance. To see you live your life and then to get to experience the craft and wisdom with which you write about your life is such a joy for me, dear friend. And The Message was such an important book for me too, and I loved seeing what you brought out in it. I think essay is your metier and can’t wait for your book. ☮️➕🙏🏻